Vieta's formulas

In mathematics, Vieta's formulas are formulas that relate the coefficients of a polynomial to sums and products of its roots. Named after François Viète (more commonly referred to by the Latinised form of his name, Franciscus Vieta), the formulas are used specifically in algebra.

Contents |

The Laws

Basic formulas

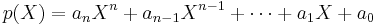

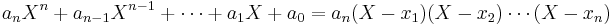

Any general polynomial of degree n

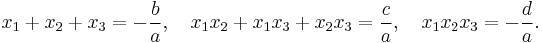

(with the coefficients being real or complex numbers and an ≠ 0) is known by the fundamental theorem of algebra to have n (not necessarily distinct) complex roots x1, x2, ..., xn. Vieta's formulas relate the polynomial's coefficients { ak } to signed sums and products of its roots { xi } as follows:

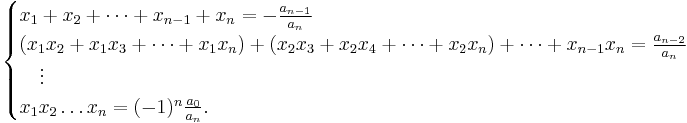

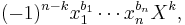

Equivalently stated, the (n − k)th coefficient an−k is related to a signed sum of all possible subproducts of roots, taken k-at-a-time:

for k = 1, 2, ..., n (where we wrote the indices ik in increasing order to ensure each subproduct of roots is used exactly once).

The left hand sides of Vieta's formulas are the elementary symmetric functions of the roots.

Generalization to rings

Vieta's formulas are frequently used with polynomials with coefficients in any integral domain R. In this case the quotients  belong to the ring of fractions of R (or in R itself if

belong to the ring of fractions of R (or in R itself if  is invertible in R) and the roots

is invertible in R) and the roots  are taken in an algebraically closed extension. Typically, R is the ring of the integers, the field of fractions is the field of the rational numbers and the algebraically closed field is the field of the complex numbers.

are taken in an algebraically closed extension. Typically, R is the ring of the integers, the field of fractions is the field of the rational numbers and the algebraically closed field is the field of the complex numbers.

Vieta's formulas are useful in this situation, because they provide relations between the roots without to have to compute them.

For polynomials over a commutative ring which is not an integral domain, Vieta's formulas may be used only when the  's are computed from the

's are computed from the  's. For example, in the ring of the integers modulo 8, the polynomial

's. For example, in the ring of the integers modulo 8, the polynomial  has four roots 1, 3, 5, 7, and Vieta's formulas are not true if, say,

has four roots 1, 3, 5, 7, and Vieta's formulas are not true if, say,  and

and  .

.

Example

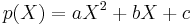

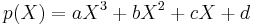

Vieta's formulas applied to quadratic and cubic polynomial:

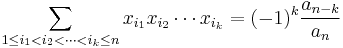

For the second degree polynomial (quadratic)  , roots

, roots  of the equation

of the equation  satisfy

satisfy

The first of these equations can be used to find the minimum (or maximum) of p. See second order polynomial.

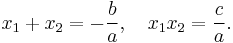

For the cubic polynomial  , roots

, roots  of the equation

of the equation  satisfy

satisfy

Proof

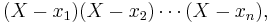

Vieta's formulas can be proved by expanding the equality

(which is true since  are all the roots of this polynomial), multiplying the factors on the right-hand side, and identifying the coefficients of each power of

are all the roots of this polynomial), multiplying the factors on the right-hand side, and identifying the coefficients of each power of

Formally, if one expands  the terms are precisely

the terms are precisely  where

where  is either 0 or 1, accordingly as whether

is either 0 or 1, accordingly as whether  is included in the product or not, and k is the number of

is included in the product or not, and k is the number of  that are excluded, so the total number of factors in the product is n (counting

that are excluded, so the total number of factors in the product is n (counting  with multiplicity k) – as there are n binary choices (include

with multiplicity k) – as there are n binary choices (include  or X), there are

or X), there are  terms – geometrically, these can be understood as the vertices of a hypercube. Grouping these terms by degree yields the elementary symmetric polynomials in

terms – geometrically, these can be understood as the vertices of a hypercube. Grouping these terms by degree yields the elementary symmetric polynomials in  – for Xk, all distinct k-fold products of

– for Xk, all distinct k-fold products of

History

As reflected in the name, these formulas were discovered by the 16th century French mathematician François Viète, for the case of positive roots.

In the opinion of the 18th century British mathematician Charles Hutton, as quoted in (Funkhouser), the general principle (not only for positive real roots) was first understood by the 17th century French mathematician Albert Girard; Hutton writes:

...[Girard was] the first person who understood the general doctrine of the formation of the coefficients of the powers from the sum of the roots and their products. He was the first who discovered the rules for summing the powers of the roots of any equation.

See also

- Newton's identities

- Elementary symmetric polynomial

- Symmetric polynomial

- Content (algebra)

- Properties of polynomial roots

- Gauss–Lucas theorem

- Rational root theorem

References

- Funkhouser, H. Gray (1930), "A short account of the history of symmetric functions of roots of equations", American Mathematical Monthly (Mathematical Association of America) 37 (7): 357–365, doi:10.2307/2299273, JSTOR 2299273

- Vinberg, E. B. (2003), A course in algebra, American Mathematical Society, Providence, R.I, ISBN 0821834134

- Djukić, Dušan, et al. (2006), The IMO compendium: a collection of problems suggested for the International Mathematical Olympiads, 1959-2004, Springer, New York, NY, ISBN 0387242996